1-Ken, in your book Into the Woods-My Life in Forestry you offer excellent insights into your very early interest in forests and the natural environment and that your Dad worked in the Timmins area in the mining sector. As a result, do you think you have a special attachment to northeastern Ontario?

Ans. Not from my father, I was only about 4 yrs. when I remember him talking about his time in the Timmins area. My interest in northeastern Ontario’s forests came largely from my initial experience there in 1951 when I visited Cochrane with the Assistant Director ( Andy Leslie) of the Research Division of Lands & Forests at Maple; in 1956 when with Bob Carman we located what became the Swastika Nursery in the Englehart Forest Management Unit (EMU). Then in 1965 I transferred the IV year Silviculture week to the EMU from St. Williams. Also, travel to northeastern Ontario from Toronto was very accessible by road and rail (Ontario Northland). Even back then when I first found out (1953) about the post glacial period of warming some 4,000 or so years ago I was certain in another period of climate warming those black spruce wetlands will be more productive.

2.-You wrote that at the age of 15-16 you were convinced that forestry was the path for you. It’s more common these days that young people keep their options open longer or even have more than one career in their working lives. Do you have any advice for young people considering the myriad of academic choices and subsequent careers?

Ans. I realize that for many young persons, especially in their late “teens” are subject to many influences from parents and their peers affecting a decision about which career path to take. Say the person has a broad area of interest - science, technology, finance or the humanities I would usually suggest they start by choosing an introductory program or course which would give them a “feel” for a future career in a particular direction. There are now such a plethora of educational programs and levels of institutions available that I can really only relate to the period of the 1950-1960’s. For example, the curriculum in forestry during much of that period besides forestry courses, had courses in botany, zoology, English, physics, chemistry, mathematics, economics, commercial law, French or German and modern world history. In addition, for a young person interested in, or with some outdoor experience, a program with such a component might be attractive. Lastly, if there is someone such as a family friend or acquaintance whose work could provide some insight if not practice this could provide an opportunity to get to know some aspects of their career.

3.-At some time, early in our careers, we occasionally found ourselves just a little bit over our heads, do you have any recollections of those times?

-What is the best advice you can give to a young forester/forest technician just starting out?

Ans. I would suggest they listen to an older more experienced person, who may or may not be associated with them in their workplace, about their experiences. This can often be in informal settings such as at lunch or meetings. When I first graduated in 1951 and worked for the Ontario Department of Lands & Forests I not only had the benefit of travelling with senior foresters in the Research Division and listening to them about their experiences. But also during the lunches in which other staff such as wildlife biologists etc participated. When I moved to the Faculty of Forestry at Toronto I reported to a senior Professor, Bob Hosie , and took over the Descriptive Dendrology course from him, about which he gave me sage advice. “Each incoming class of first year students are equally ignorant about trees and the trees don’t change so after two or three years of teaching the course the reason you want to change its organization is mainly because you’re bored”. On all these occasions I took note of the situations they recounted and their responses as they could apply to future situations I might find myself in.

Further, I gleaned much from my membership in the Soil Science Society of America which was a part of the larger American Society of Agronomy where I could acquire knowledge about new discoveries and innovations in soils and soil management which might be applicable in forestry. So, don’t shut yourself off in your “silo”.

4- While always working in the field of forestry you had a wide range of jobs including: researcher; University professor; senior public servant; high powered forest policy consultant; historian…may have missed a few… which one did you like the best and why?

Ans. Like anyone else, as one ages especially in the same workplace my interests in my career evolved. In my first years expanding my role as a teacher and researcher was paramount and this meant keeping in communication with fellow foresters in academe ( both in Canada but equally important with my colleagues in forestry colleges in the United States), and also those engaged in the practice of forestry especially in Ontario and Canada. As a result of the opportunities afforded me, primarily the fact that both the Ontario Department of Lands & Forests and its successor the Ministry of Natural Resources asked me to undertake either studies or projects every year that I was at the Faculty. For example, when I joined the Faculty in late 1952, I was asked to continue my association with Angust Hills during the following summers and in 1955 when I was going to Oxford for graduate work in tree nutrition, G.H.U. (Terk) Bayly who was the director of the Reforestation Division asked me to visit three of the nurseries, St.Williams, Midhurst and Orono and generally assess the condition of their seedlings. He then asked that when I was in the U.K. and European countries most of which had large tree planting progams far greater that Ontario’s, I should write a report on them when I returned in the summer of 1956. This I did and he responded by asking me to recommend soil management programs for the existing nurseries, assist in the evaluation of sites for new nurseries in the north and also look at existing plantations where the L&F local forester thought there was a problem. This was the origin of the nursery soil management program for Ontario and support for many graduate student projects.

By 1967, Ontario had experienced many large forest fires in the northern Boreal forest and the costs of fire fighting were high so that apart from immediate protection for the isolated, mainly indigenous communities, the L&F staff wanted to reduce the latitude (54 N) beyond which they had to respond to forest fires based on the fact that historically the Boreal forest was a natural result of fire. The possible negative effects of fire had become a political item and I was asked to study the effects of forest fires on the soil in Northern Ontario which I did in 1968 based out of Sioux Lookout. This and my work in the nurseries gave me a sense of the degree to which political debate could influence forestry decisions and practices.

As a student and during my career I was keenly aware that forestry in its full meaning was not practiced in Ontario or for that matter in most of Canada. Forest companies cut timber under provincial licences and the province attempted regeneration. It was only on Crown units where attempts by the unit’s forester to plan, harvest, regenerate, maintain and protect the forest could be found. When I was asked to take a year (1975-76) to prepare a report on forest management in Ontario the separation of planning for and harvesting the forests done by the industry was independent from the necessary planning for regeneration and other practices which are an essential part of forest management. As a result in 1977 I was asked by the Minister of Natural Resources - Frank Miller to work with Jim Lockwood Executive Director of the Forests Division to negotiate an agreement with forest companies to undertake the implementation of forest management in the fullest and professional sense. Initially, I joined Jim on an eight months leave of absence from the Faculty, but when Jim retired in 1978 I became fully responsible for the negotiations with assistance from Fred Robinson, the Senior Boreal Forester. Thus I was involved in all stages of what became the Ontario Forest Management Agreements (FMA’s) including the drafting of new legislation and the associated political involvement,

In a short answer to your question: the year I spent travelling the province in preparation for my report, “Forest Management in Ontario” and my involvement in the development of FMA’s were the most satisfying of my career in forestry.

Later, when I retired I was involved in development of the criteria for Sustainable Forest Management developed by the Canadian Standards Association and then the procedures for auditing the standard.

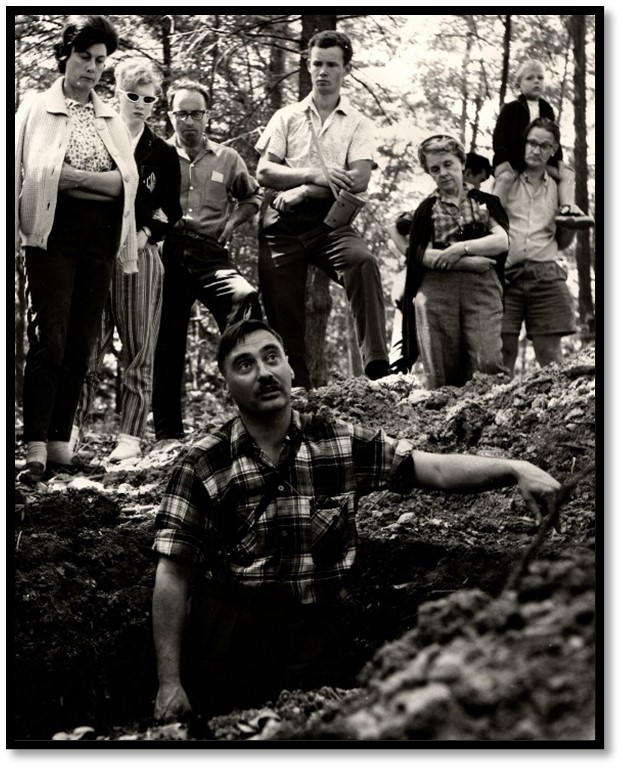

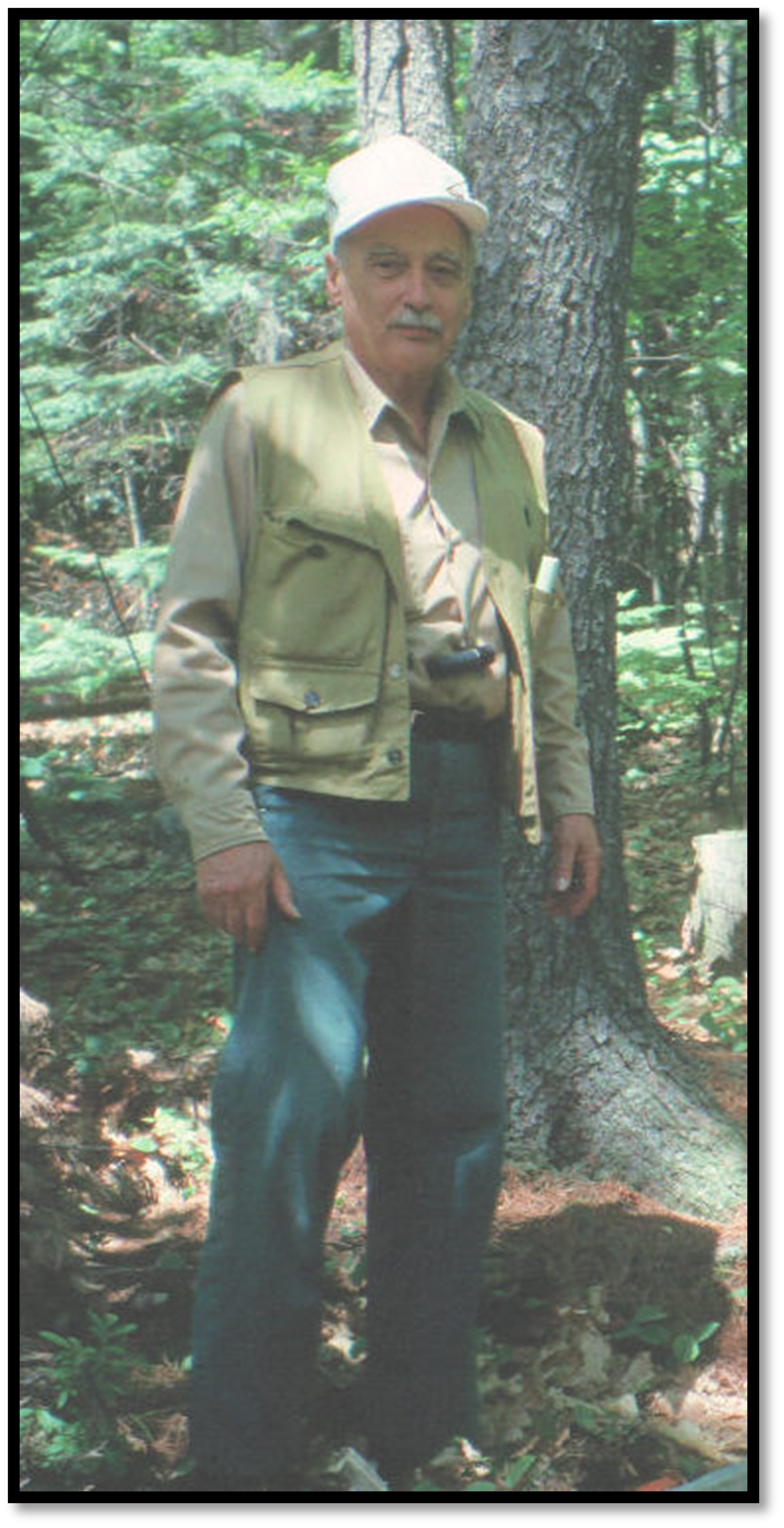

Picture 1: During the early 1960's I was involved in natural sciences education with the Toronto School Board and the development of the Albion Hills school and also with the Metropolitan Toronto Region Conservation Authority (MTRCA) and their areas particularly the Greenwood C.A. north of Pickering. Twice a year I did hikes for the public on a Sunday focussing on trees, succession and soils. This is a photo taken on one of these "hikes" at the Greenwood CA probably 1961-2.

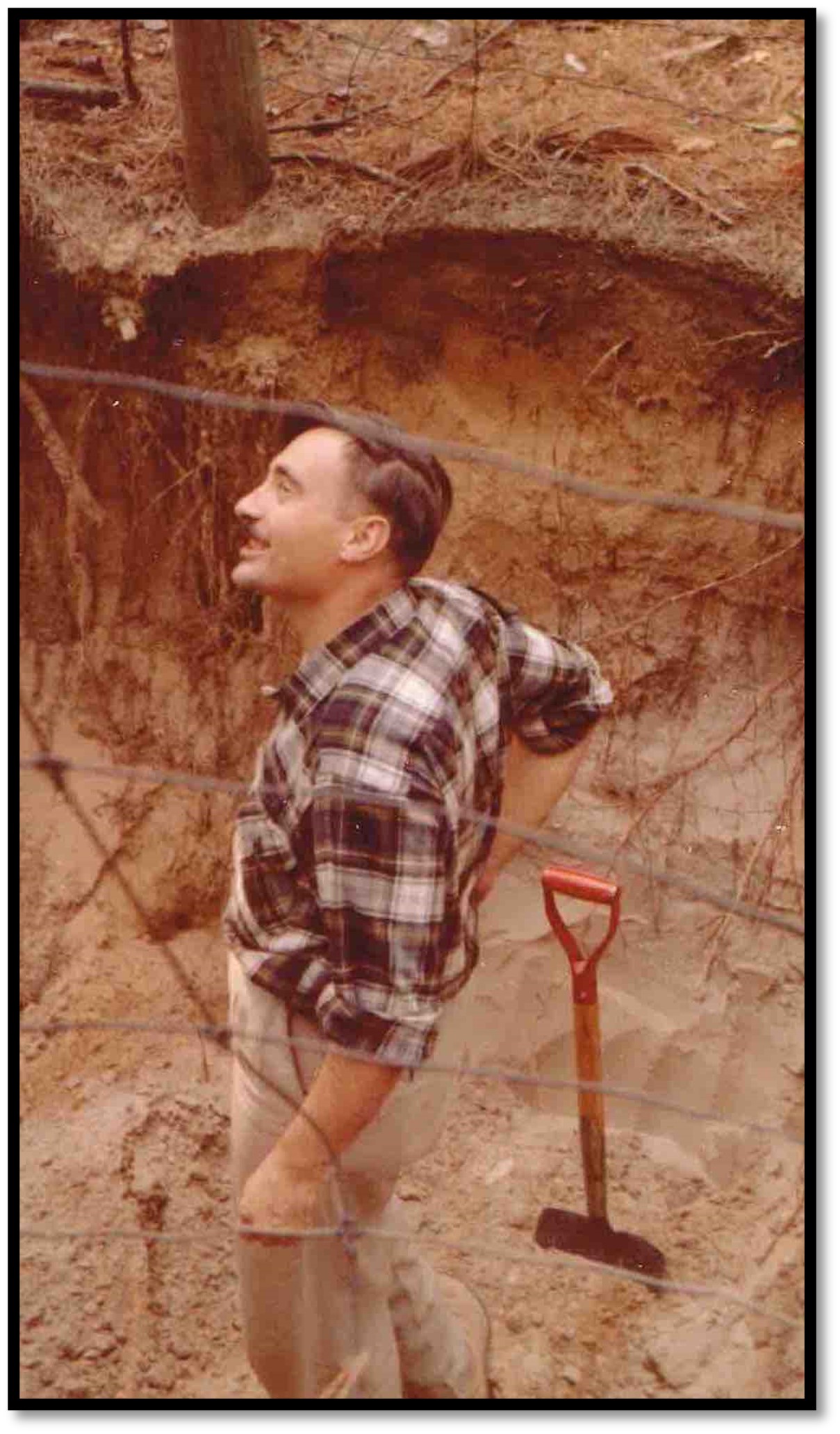

Picture 2. 1963-4. Not sure of the location but I suspect it was either at St. Williams or the Vivian Tract of the York Regional Forest.

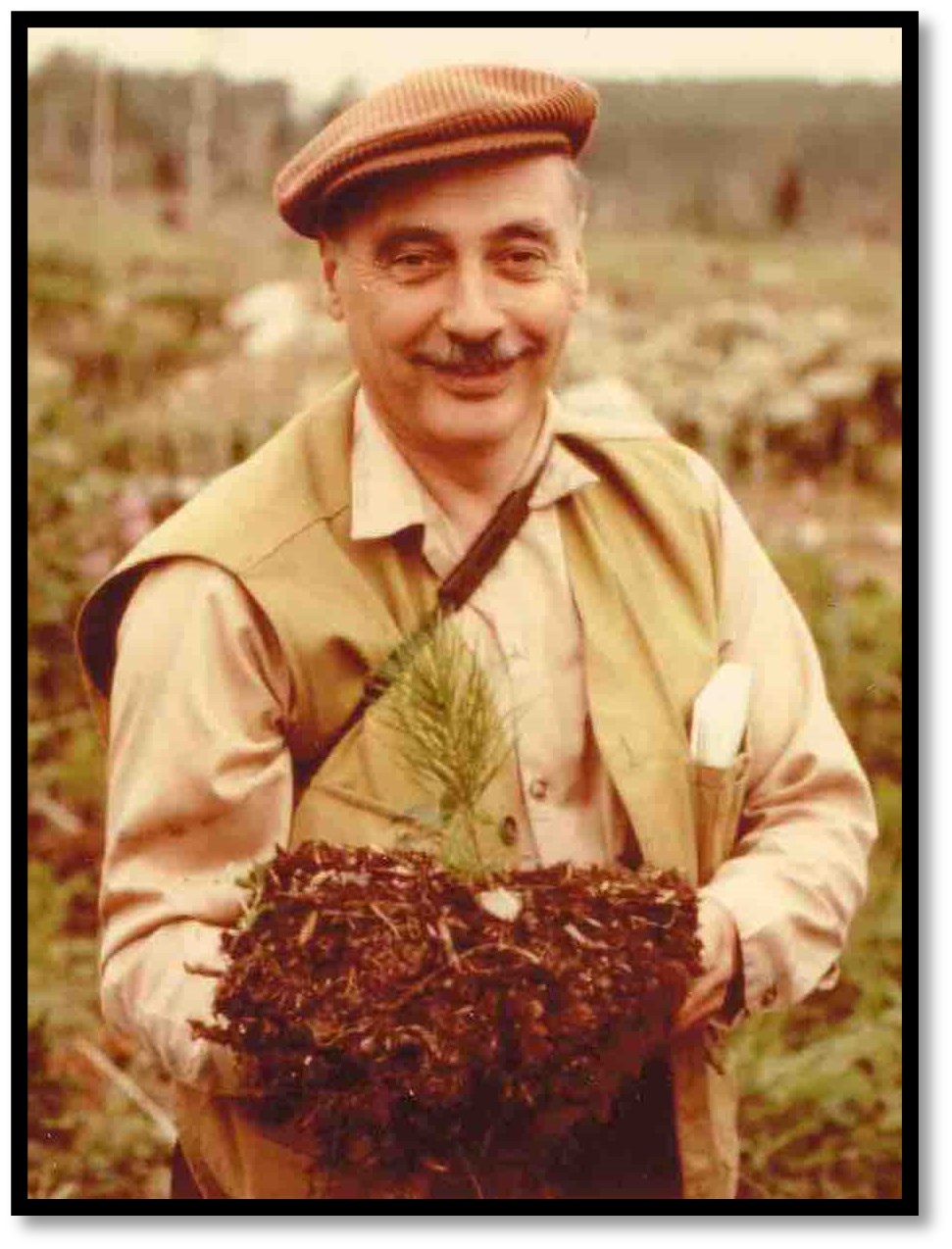

Picture 3. 1974? I think this was at the Englehart Management Unit, Kirkland Lake

Picture 4. 1977 Location was in the Minden Management Unit.

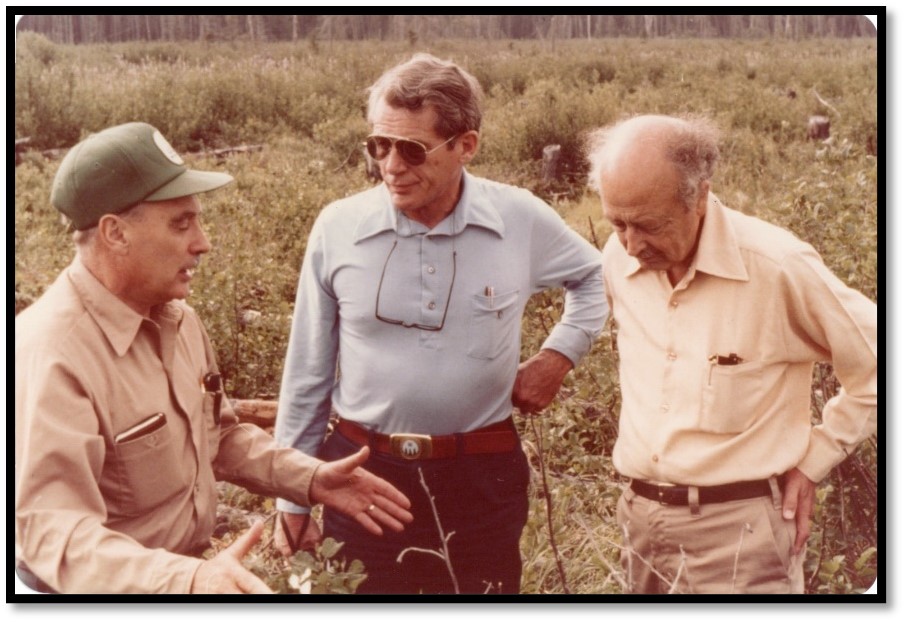

Picture 5. 1980 Location Spruce Falls P&P Co. July, 1980 and I'm explaining to Minister Jim Auld and Deputy Keith Reynolds the implications of the application of Forest Management Agreements (FMA's) in the field

Picture 6. 2005 Soil/site workshop Iroquois Falls.

Interviewed by Jim Farrell, 2023.